Testimonials from Riker's Island

My definition of a trauma-informed child serving system

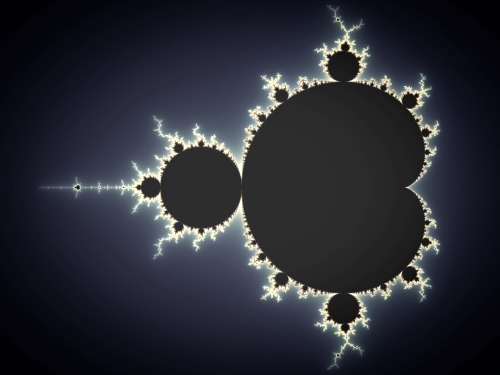

Revisiting the Fractal Nature of Relationships and the Therapeutic Process

NY1 Covers Community Discussion about Eric Garner

Appearance on The Adopting Teens & Tweens Radio Forum

The HEARTS Program is promoted within Mount Sinai Health System

Helping the NYC Citywide Oversight Committee & Upcoming Talk

Lessons on the Psychology of Trauma in Korea’s Response to the Sewol Tragedy

Upcoming Event for the Korean Community about Sewol

The Nurturance of Being Known

Contributing to Today.com's "In sickness and in health? Wife's illness tied to divorce"

Auction! 2-Night Stay @ Trump Hotel Central Park April 11 & 12, 2014

Moms

random inspiration from therapy

A snippet of a recent training on trauma-informed practices

Navigating Conversational Currents

On Patrick Stewart's video about domestic violence and trauma

Bryan Stevenson's TED Talk on Injustice