I’ve been thinking a lot about managing difficult conversations recently because of some intense family work I’ve been doing and thought I’d write out my ideas to help me understand them. Please feel free to comment and ask for clarification to help me further my thinking.

The gist of what I think heavily borrows from three books but with a trauma twist: Difficult Conversations, Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work; and Hold Me Tight.

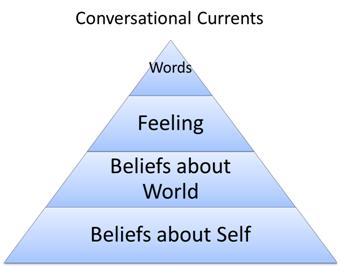

So the bulk of what I seem to be doing in therapy nowadays when it comes to conversations is to help people attune to the multiple streams of discourse that are occurring simultaneously in any and all conversations. The most superficial stream is the actual topic and the words spoken. This current is the visible surface of every conversation. Under that is the current of feelings that are still visible from above but still sometimes requires the intentional light of attention to discover. Under that lies a deeper current about beliefs, particularly about the world and one’s values in the world. Here lie beliefs about how the world should work, how others should behave and how others should treat each other. The deepest and most difficult to find current of conversation is about beliefs about the self. What is this conversation implying about who I am as a person and my value as a person? Is this conversation making me look stupid, wrong, mean or smart, right, or otherwise virtuous?

Problems arise when the deeper currents are becoming agitated but the actual topic of conversation doesn’t move to focus on the underlying currents. Conversations about politics or religion are clear examples of when beliefs about the world become primary, but they are generally avoided because they agitate the currents of self-value, whether a person is fundamentally good and moral. Between parents and children, some conversations seem to be about mundane problems or challenges (like getting homework done or setting a curfew), but they suddenly and unexpectedly blow up because the conversation triggers feelings of “I’m a horrible parent” or “They’re treating me like a child and I am not a baby!” The tricky thing to do is to know when certain currents are taking primacy in a conversation and then being able to have conversations from that current.

When trauma is somehow in the picture (either trauma in the child, parent, or both), the waters become even choppier. Trauma has a tendency of hijacking any conversation, especially when there is strife, stress, or intensity. Trauma tends to escalate feelings very quickly too because one’s self-protective alarm response is easily triggered and rapidly mobilizes a fight or flight response. Trauma also gets deeply embedded in the currents of belief: the world is not safe, you are dangerous or scary, I can’t trust anyone, I don’t deserve love, or I deserve to be hurt.

In these situations, it’s even more important for people to watch for how trauma is distorting or impacting the current of conversation. And, when the conversation starts to feel heated, confusing, or frustrating, then I strongly believe that people need to take a pause to figure out what is happening at all currents of the conversation. Sometimes, this can be very hard to figure out, and people may not feel safe enough to share the deeper currents. That’s why a sensitive therapist can help people articulate the currents and do so in a safe way.

It’s still very hard, though; trust me.